What does it mean for a city to transform?

As an environmental justice advocate and student, the words “urban transformation” immediately raise some red flags for the work of justice and inclusion. While in Medellín, I wanted to know for whom was the city was transforming, and how? Many times, when an “urban transformation” takes place in a city in the US, the most marginalized communities never see the benefits of the changes made. Often the shifts come at the expense of those who have lived there the longest, or are made on the backs of the community with their labor and support and then, they are discarded as if they were never there at all.

When I visited Medellín as part of a urban planning and architecture student delegation, the research of Isabelle Anguelovski was fundamental to my approach. Dr. Anguelovski has written extensively about environmental gentrification across the globe and specifically about the tensions around green infrastructure planning in Medellín. She writes “Our research in Medellín illustrates that local governments, planners, and building companies and developers often promote new environmental projects in ways that transform existing urban development patterns to produce socio‐spatial control and environmental, distributional and procedural inequalities” (pg. 20, 2018). With these tensions in mind, the projects of transformation across the city always seemed a little bittersweet.

We worked in partnership with Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana professors and students, and were accompanied on each journey by local community leaders and organizers. Largely because of these relationships, the transformative projects we witnessed felt beneficial to all. Dr. Anguelovski’s research centers on the greenbelt (Jardín Circunvalar) that wraps the mountains and has acted as an attempt to halt development in high altitude areas. The following projects are in various locations around the city and feel important to share. Thank you to the community leaders and activists we were able to interact with and the amazing students and professors for these connections.

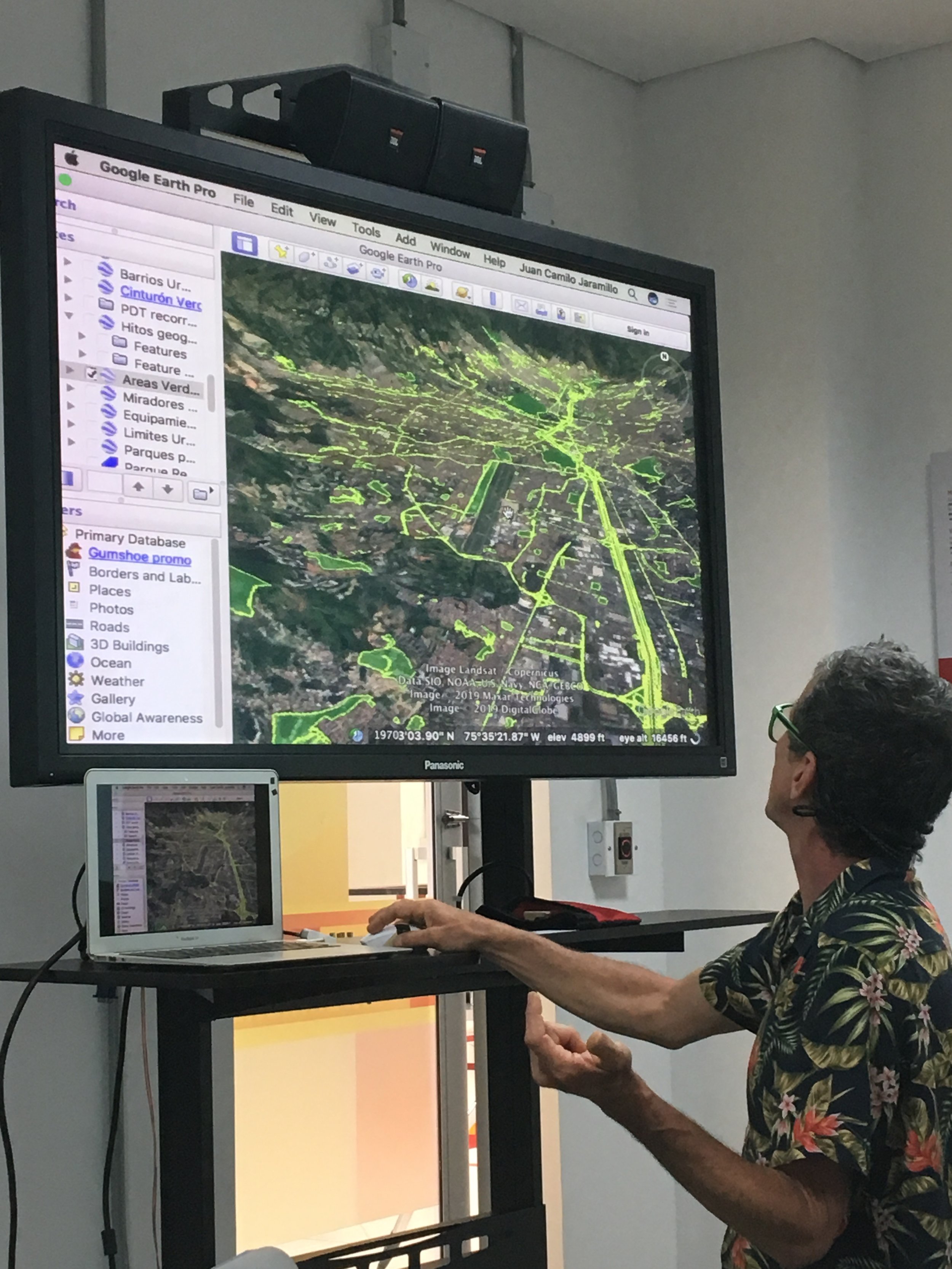

The city shown from high elevation with electric wires and lighting provided by the city’s utility company.

Empresas Públicas de Medellín (EPM) provides water and electric to a majority of homes across the city

The public utility company, known as EPM, acts as a social transformer for the residents of Medellin. With the low-income communities oftentimes building their own homes out of materials they find and bring with them from the rural areas, they build often where there is still space remaining. These are usually at very high and steep elevations. While government officials also tear down handmade homes, when they succeed in building them, EPM must do their best to provide electric and water and sewage to all residents.

Unidades de Vida Articulada (UVAs)

Unidades de Vida Articulada (UVAs) are projects funded by EPM and designed by various teams of Colombian architects that open up formerly closed water tanks and the surrounding areas to community members. Here we saw classes being taught, sports, children playing in fountains, and a connection with the water which was hidden before.

Unidades de Vida Articulada (UVAs) are projects funded by EPM and designed by various teams of Colombian architects that open up formerly closed water tanks and the surrounding areas to community.

Community Gardens

A garden in a community that was relocated to high mountain public housing without much access to employment or public transit.

urban agriculture projects and gardens

These gardens were built around the idea that women are the ones who take care of the future and of the earth. Meeting and speaking with the women who ran these gardens and their homes were amazing and felt incredibly powerful to speak with such radical feminist caretakers and gardeners! While there is trauma from being relocated and learning a new location (once again for many people) the women in this community are able to show strength and resistance as well as resilience for their future.

Watch a video of a design charrette with students, filmmakers and community organizers from Communa 8 at Parque Biblioteca Leon de Greiff in Medellin, Colombia.